I posted yesterday about the urgent need to change education paradigms.

As such it feels fitting to final re-post this post from Gloria’s blog here:

Have you noticed there’s a lot of hullabaloo about Finland’s education system lately? I’ve been paying attention to what the Finns have been doing for a couple years now, but it is only after reading an essay by Sam Abrams I’ve thought to pay attention to Finland’s neighbour Norway.

Norway and Finland have some similarities. They are neighbouring countries that each take up about 350 000 square kilometres with populations around 5 million and about 10 percent foreign born in Norway and 4 percent in Finland. A notable difference, however, is that Norway has a significantly higher Gross Domestic Product.

Norway has oil. Finland has trees. Since the 1970s, Norway has focused intensely on developing their oil and gas resources which have risen to 45% of their total exports and 20% of their GDP. These efforts have provided Norway with bragging rights over being the fifth largest oil exporter and third largest gas exporter in the world.

Meanwhile, Finland in 1971 realised that their natural resources, largely timber, weren’t going to cut it. They needed to modernize their economy and to do it they were going to have to improve their schools. In other words, they were going to have to focus intensely on developing their children’s brains.

To do this, Finland focused on reducing class size, improving formative assessment practices, increasing teacher pay & notoriety, and requiring all teachers to complete a master’s program. Finnish teachers use a relatively concise national curriculum to guide them in creating curriculum and assessment at the local level, and very little time, effort and resources are wasted with standardised testing; in fact, the only time a Finnish student would ever be required to write a standardized exam is if a high school senior planned on attending university (National Matriculation Examination). Finland has worked worked meticulously to ensure equity and opportunity thus reducing the number of Finnish children who live in poverty to 1 in 25.

Today, Finland’s education system is considered to be one of the best in the world.

Conversely, despite Norway’s similar demographics, their education reforms have followed a very different path than Finland’s:

- Their class sizes tend to be larger

- They struggle to find enough qualified teachers

- Rather than focusing on better trained teachers, Norway has thrown millions of dollars at a teacher preparation program similar to Teach for America called Teach First Norway where teachers get mere weeks of training.

- They implemented a national standardized testing system of accountability

- They have placed more time, effort and resources on summative assessment such as tests and grades.

- Based on PISA scores, Norway’s education system falls somewhere around mediocre.

So why is comparing and contrasting Finland and Norway important?

Upon hearing about the progress Finland has had with their education system, many policy-makers in other countries may be inclined to point towards the Finns smaller, more homogenous population as the primary reason for their successes in the classroom. That Norway and Finland can share such similarities in population and yet differ with their education systems may be enough proof that policy choices, rather than demographics, can play a potentially larger role in a nation’s educational success.

In Alberta, Canada, we have dedicated a considerable amount of time, effort and resources on becoming the world’s second largest exporter and fourth largest producer of natural gas while simultaneously helping Canada become the seventh largest producer of oil, just three spots ahead of Norway. While debating whether this is something Alberta or Norway should be proud of or not may make for an interesting discussion, such a dialogue is not the purpose of this post.

Let us acknowledge that the world is changing and so must our education system in order to prepare our children for a future we can not predict.

This is not up for debate.

Regions like Norway and Alberta run the risk of being blinded by what some have coined a “resource curse” or a paradox of plenty. A dependency on oil and gas can leave us grossly susceptible to excessive revenue volatility — things are glorious in the booms but down-right scary in the busts. It’s not unheard of to hear during these busts calls to balance the budget on the back of cutting spending on education, which ends up being the equivalent to a farmer selling the top-soil to pay the bills.

While regions like Alberta and Norway can afford to pay less time, effort and resources on their education systems, Finland’s lack of resources has forced them to invest “laser-like” attention on nurturing theirs. The good news is that if Finland can do this with less, the abundance of wealth in regions like Norway and Alberta can be used to do the same.

So if Finland’s successes in the classroom are less about their inherent Finnish characteristics and more about their policies, then it might be advantageous to identify how the Finnish differ from conventional education reforms.

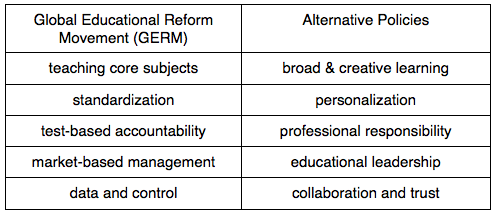

Pasi Sahlberg is a leading educator from Finland and former senior adviser in Finland’s Ministry of Education who writes and speaks about what the world can learn from Finland. The chart below contrasts what Sahlberg coins as The Global Education Reform Movement (GERM) with alternative policies that Finland has successfully enrolled:

In his post On a Road to nowhere, Sahlberg explains:

English education policies rely on more choice, tougher competition, intensified standardised testing and stronger school accountability. These are the key elements of the policies that were dominant in the United States, New Zealand, Japan and parts of Canada and Australia a decade or so ago. Available PISA data reveals the impact of these education policies on students’ learning between 2000 and 2009. The overall learning trend in all these countries is consistently declining. That is a road to nowhere. Many governments are taking note of the 2009 PISA results, but they are rather selective in reporting of the education systems that are doing well in PISA. Finland has been one of the few consistently high performing systems in PISA’s 10-year history. Significantly, Finland has not employed any of the market-based educational reform ideas in the ways that they have been incorporated into the education policies of many other nations, including the United States and England.

Finland’s successful pursuit of policies driven by diversity, trust, respect, professionalism, equity, responsibility and collaboration refute every aspect of reforms that focus on choice, competition, accountability and testing that are being expanded in countries around the world.

In short, it’s time to put ideology aside and focus intensely on the paradoxes of the Finland phenomenon.

University of Helsinki – Faculty of Behavioral Sciences, Department of Teacher of Education Research Report No 347 Authors: Jarkko Hautamäki, Sirkku Kupiainen, Jukka Marjanen, Mari-Pauliina Vainikainen and Risto Hotulainen

Signs of declining results 15 y

The change between the year 2001 and year 2012 is significant. The level of students’ attainment has declined considerably.The difference can be compared to a decline of Finnish students’ attainment in PISA reading literacy from the 539 points of PISA 2009 to 490 points, to below the OECD average.

‘Since 1996, educational effectiveness has been understood in Finland to include not only subject specific knowledge and skills but also the more general competences which are not the exclusive domain of any single subject but develop through good teaching along a student’s educational career. Many of these, including the object of the present assessment, learning to learn, have been named in the education policy documents of the European Union as key competences which each member state should provide their citizens as part of general education (EU 2006).

In spring 2012, the Helsinki University Centre for Educational Assessment implemented a nationally representative assessment of ninth grade students’ learning to learn competence. The assessment was inspired by signs of declining results in the past few years’ assessments. This decline had been observed both in the subject specific assessments of the Finnish National Board of Education, in the OECD PISA 2009 study, and in the learning to learn assessment implemented by the Centre for Educational Assessment in all comprehensive schools in Vantaa in 2010.

The results of the Vantaa study could be compared against the results of a similar assessment implemented in 2004. As the decline in students’ cognitive competence and in their learning related attitudes was especially strong in the two Vantaa studies, with only 6 years apart, a decision was made to direct the national assessment of spring 2012 to the same schools which had participated in a respective study in 2001.

Girls performed better

The goal of the assessment was to find out whether the decline in results, observed in the Helsinki region, were the same for the whole country. The assessment also offered a possibility to look at the readiness of schools to implement a computer-based assessment, and how this has changed during the 11 years between the two assessments. After all, the 2001 assessment was the first in Finland where large scale student assessment data was collected in schools using the Internet.

The main focus of the assessment was on students’ competence and their learning-related attitudes at the end of the comprehensive school education, but the assessment also relates to educational equity: to regional, between-school, and between- class differences and to the relation of students’ gender and home background to their competence and attitudes.

The assessment reached about 7800 ninth grade students in 82 schools in 65 municipalities. Of the students, 49% were girls and 51% boys. The share of students in Swedish speaking schools was 3.4%. As in 2001, the assessment was implemented in about half of the schools using a printed test booklet and in the other half via the Internet. The results of the 2001 and 2012 assessments were uniformed through IRT modelling to secure the comparability of the results. Hence, the results can be interpreted to represent the full Finnish ninth grade population.

Girls performed better than boys in all three fields of competence measured in the assessment: reasoning, mathematical thinking, and reading comprehension. The difference was especially noticeable in reading comprehension even if in this task girls’ attainment had declined more than boys’ attainment. Differences between the AVI-districts were small.

Decline of attainment

The impact of students’ home-background was, instead, obvious: the higher the education of the parents, the better the student performed in the assessment tasks. There was no difference in the impact of mother’s education on boys’ and girls’ attainment. The between-school-differences were very small (explaining under 2% of the variance) while the between-class differences were relatively large (9 % – 20 %). The change between the year 2001 and year 2012 is significant. The level of students’ attainment has declined considerably. The difference can be compared to a decline of Finnish students’ attainment in PISA reading literacy from the 539 points of PISA 2009 to 490 points, to below the OECD average. The mean level of students’ learning-supporting attitudes still falls above the mean of the scale used in the questions but also that mean has declined from 2001. The mean level of attitudes detrimental to learning has risen but the rise is more modest.

Girls’ attainment has declined more than boys’ in three of the five tasks. There was no gender difference in the change of students’ attitudes, however. Between-school differences were un-changed but differences between classes and between individual students had grown. The change in attitudes—unlike the change in attainment—was related to students’ home background: The decline in learning-supporting attitudes and the growth in attitudes detrimental to school work were weaker the better educated the mother. Home background was not related to the change in students’ attainment, however. A decline could be discerned both among the best and the weakest students.

Deeper cultural change

The results of the assessment point to a deeper, on-going cultural change which seems to affect the young generation especially hard. Formal education seems to be losing its former power and the accepting of the societal expectations which the school represents seems to be related more strongly than before to students’ home background.

The school has to compete with students’ self-elected pastime activities, the social media, and the boundless world of information and entertainment open to all through the Internet. The school is to a growing number of young people just one, often critically reviewed, developmental environment among many. The change is not a surprise, however. A similar decline in student attainment has been registered in the other Nordic countries already earlier.

It is time to concede that the signals of change have been discernible already for a while and to open up a national discussion regarding the state and future of the Finnish comprehensive school that rose to international acclaim due to our students’ success in the PISA studies.’

Source: University of Helsinki – Faculty of Behavioral Sciences, Department of Teacher of Education Research Report No 347 Authors: Jarkko Hautamäki, Sirkku Kupiainen, Jukka Marjanen, Mari-Pauliina Vainikainen and Risto Hotulainen

Thanks for the info!

View of Finnish teachers versus view of Pasi Sahlberg

Oxford- Prof. Jennifer Chung ( AN INVESTIGATION OF REASONS FOR FINLAND’S SUCCESS IN PISA (University of Oxford 2008).

“Many of the teachers mentioned the converse of the great strength of Finnish education (= de grote aandacht voor kinderen met leerproblemen) as the great weakness. Jukka S. (BM) believes that school does not provide enough challenges for intelligent students: “I think my only concern is that we give lots of support to those pupils who are underachievers, and we don’t give that much to the brightest pupils. I find it a problem, since I think, for the future of a whole nation, those pupils who are really the stars should be supported, given some more challenges, given some more difficulty in their exercises and so on. To not just spend their time here but to make some effort and have the idea to become something, no matter what field you are choosing, you must not only be talented like they are, but work hard. That is needed. “

Pia (EL) feels that the schools do not motivate very intelligent students to work. She thinks the schools should provide more challenges for the academically talented students. In fact, she thinks the current school system in Finland does not provide well for its students. Mixed-ability classrooms, she feels, are worse than the previous selective system: “ I think this school is for nobody. That is my private opinion. Actually I think so, because when you have all these people at mixed levels in your class, then you have to concentrate on the ones who need the most help, of course. Those who are really good, they get lazy. “

Pia believes these students become bored and lazy, and float through school with no study skills. Jonny (EM) describes how comprehensive education places the academically gifted at a disadvantage: “We have lost a great possibility when we don’t have the segregated levels of math and natural sciences… That should be once again taken back and started with. The good talents are now torturing themselves with not very interesting education and teaching in classes that aren’t for their best.

Pia (EL) finds the PISA frenzy about Finland amusing, since she believes the schools have declined in recent years: “I think [the attention] is quite funny because school isn’t as good as it used to be … I used to be proud of being a teacher and proud of this school, but I can’t say I ’m proud any more.”

Aino (BS) states that the evenness and equality of the education system has a “dark side.” Teaching to the “middle student” in a class of heterogeneous ability bores the gifted students, who commonly do not perform well in school. Maarit (DMS) finds teaching heterogeneous classrooms very difficult. She admits that dividing the students into ability levels would make the teaching easier, but worries that it may affect the self-esteem of the weaker worse than a more egalitarian system Similarly, Terttu (FMS) thinks that the class size is a detriment to the students’ learning. Even though Finnish schools have relatively small class sizes, she thinks that a group of twenty is too large, since she does not have time for all of the students: “You don’t have enough time for everyone … All children have to be in the same class. That is not so nice. You have the better pupils. I can’t give them as much as I want. You have to go so slowly in the classroom.” Curiously, Jukka E. (DL) thinks that the special education students need more support and the education system needs to improve in that area.

Miikka (FL) describes how he will give extra work to students who want to have more academic challenges, but admits that “they can get quite good grades, excellent grades, by doing nothing actually, or very little.” Miikka (FL) describes discussion in educational circles about creating schools and universities for academically talented students: 3 Everyone has the same chances…One problem is that it can be too easy for talented students. There has been now discussion in Finland if there should be schools and universities for talented students… I think it will happen, but I don’t know if it is good, but it will happen, I think so. I am also afraid there will be private schools again in Finland in the future … [There] will be more rich people and more poor people, and then will come so [many] problems in comprehensive schools that some day quite soon … parents will demand that we should have private schools again, and that is quite sad.

Linda (AL), however, feels the love of reading has declined in the younger generation, as they tend to gravitate more to video games and television. Miikka (FL), also a teacher of mother tongue, also cites a decline in reading interest and an increase of video game and computer play. Saij a (BL) agrees. As a teacher of Finnish, she feels that she has difficulty motivating her students to learn: “I think my subject is not the … easiest one to teach. They don’t read so much, newspapers or novels.” Her students, especially the boys, do not like their assignments in Finnish language. She also thinks the respect for teachers has declined in this past generation. Miikka (FL) also thinks his students do not respect their teachers: “They don’t respect the teachers. They respect them very little … I think it has changed a lot in recent years. In Helsinki, it was actually earlier. When I came here six years ago, I thought this was heaven. I thought it was incredible, how the children were like that after Helsinki, but now I think it is the same.

Linda (AL) notes deficiency in the amount of time available for subjects. With more time, she would implement more creative activities, such as speech and drama, into her lessons. Saij a (BL) also thinks that her students need more arts subjects like drama and art. She worries that they consider mathematics as the only important subject. Shefeels countries such as Sweden, Norway, and England have better arts programs than in Finnish schools. Arts subjects, according to Saij a, help the students get to know themselves. Maarit (DMS), a Finnish-speaker, thinks that schools need to spend more time cultivating social skills.